A Greater Administration of Lower Interests

A Greater Administration of Lower Interestsnew york report

now i was supposed to go to the city that should determine my future career and life. my friends all agreed that new york was “the” city for me. i wasn’t so much leaving as being dispatched, equipped with euphoric prophecies about how my life would evolve from this important juncture.

a new attitude towards life, new insights, love, money, and success were all predicted for me. everyone regarded my working with the brand new upper east side gallerist as a stroke of genius. the flight was a breeze: direct connection berlin-new york, six half-seen movies, among them many of my favorites, like the nanny diaries, where scarlett johansson plays the nanny for the former director of gagosian gallery. this is exactly what i’d like to watch for hours and hours everyday. scarlett johansson tries over and over to explain to all of us the right life in the wrong, in the prettiest pictures, with the most beautiful people, in the brightest sunshine. i’d already heard about the perpetually clear weather and impressive light. ungodly conditions (like the weather) can be embellished in film just as easily as in words.

a good way to get to know my new home: the upper east side. i fast-forwarded through the wizard of oz, already looking forward to the new john waters book i was going to buy as soon as i got there.

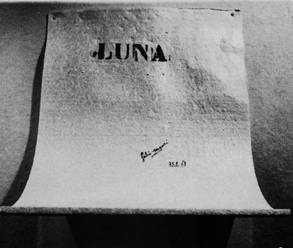

i’d kind of forgotten that people treat new york like it’s the epicenter of both art-history and the contemporary art world, and a show there is something kind of special, as if you should send your parents a postcard to let them know that things are going ok, and that they don’t need to worry. this fact i either forgot or repressed. i totally managed to ignore it, despite people telling me things like “now things are about to get real,” because otherwise i would’ve been even more afraid before leaving. for this very reason, i hadn’t prepared for the show at all, instead packing up a few not especially connected things that i imagined i might be able to put on display.

the first thing on my social calendar was supposed to be a welcome bbq in the gallery where i could also invite my old music friends. even the germans that were passing through or in love came by. every time i responded, “i have no idea,” to the question of what i was showing, i saw panic stricken faces. some people warned me that night not to blow another opportunity, and actually no one found it especially clever that i had arrived with little to no preparation. this was just not done here, they informed me. in addition to all the transgressions you were supposed to have packed (people actually suggested this to me before leaving), the city was expecting real honest work … at the very minimum. at first i felt pretty good about it—that i was completely right, and that i’d done everything exactly as i should have. the gallerist had always been very relaxed when we discussed the show, and he never gave me the feeling that he expected too much from me. my first idea to show “alien” II and III in the gallery seemed to be fine with him. he even made it explicitly clear that he didn’t want a “conventional show,” even though i was always wondering what that could possibly be; i always thought that the art i wanted to make, or the work of the people we liked in common had nothing to do with that, so there was no chance that there would be any problem.

it was either that i hadn’t been listening or that i’d only half-listened on purpose so that i wouldn’t have to deal with it. anyways, the next day i was to report to the gallery.

i’d bought some decoy birds at the hunting store on friedrichstrasse the day before, and with great delight, i set them up for the gallerist on his desk. then slowly it became clear that maybe i’d expected too much from the flocked plastic magpies. unable to inspire rapture in him, they were quickly deposited behind the ikea paravan that cordoned off the gallery space, returned back to the cage that went with them. sort of irritated, i sat around at the desk and googled pictures of hairy men, sorting through the results while taking care that the reflection of the monitor in the office window wouldn’t give me away. killed time until lunch, panic gradually breaking out…

two weeks later:

my situation has completely changed. suddenly no trace of the non-productive attitude from the beginning—instead i found myself in the middle of a giant production process that i myself had initiated out of fear of not living up to expectations. african fabrics were bought in mass quantity. i had realized that i had really liked them in london, and i had heard that in new york you could get anything that money can buy. this was true. work in the gallery was simply organized and hierarchically controlled. the gallerist alex zachary oversaw and supervised in 163 addition to my helpless efforts, the ever-helpful gallery assistant mathew sova, who turned out to be a stroke of absolute good fortune. with his skill and intuition, he managed the whole enterprise. i asked him every five minutes what he thought was better. thank god he always had a quick answer at the ready. most likely it was for the best that he was, first of all, occupying the attention of the head boss of the gallery, and second, not in the least bit ambitious in any way. he neither saw the gallery assistant job as a springboard to artisthood (as is usually the case), nor did he really want to play a role in the periphery of the business. i fell immediately in love with him…

continuation

of course it was a little unusual that mathew and i were such close friends, also because i pretty much lived next to his desk, where day after day, for a pittance of a salary, he had to make decisions for me. one day he took me to his house—it was in a distant part of brooklyn they call “bed stuy.” “bed stuy is a world famous ghetto,” that’s what one of my other friends had told me. all the people i had recently gotten to know lived there, however, and i couldn’t imagine them in the ghetto at all. in fact, they were all actually young people with good backgrounds who had studied at harvard or columbia, and they somehow seemed to know something about every tiny remark that anyone anywhere had ever uttered. this bed stuy didn’t look anything like a ghetto, more like a district in london that i’d never been to but that looked familiar from pictures. the rents were supposed to be reasonable here and the area more or less safe. “afroamerican middle class,” a taxi driver called it on the way, as i was going there for the first time. i could never get rid of the weird feeling that i was some kind of intruder in this neighborhood, and i was always reminded of that animation from the film “princess mononoke” where that weird giant deer sets off a wave of blossoming and wilting every time he steps on green grass. i knew i was undoubtedly part of this gentrification avant-garde that had arrived to change the neighborhood forever, but people always told me that that was the city, and new york just worked like that.

actually i liked the upper east side better; i felt less guilty there. i really liked the gallery space. meanwhile, i’d had leftover silkscreens sent from london, and i had asked a japanese framer in the meaningful sounding neighborhood “prospect heights” to prepare frames wrapped in fabric, with the prints’ mat windows cut to the dimensions of art magazines.

two weeks later:

somehow suddenly the exhibition was almost finished. the last few days were extremely nerve-racking. the only thing holding me together was the speedy pseudo-ephedrine in the advil cold and sinus medicine that you can buy in any pharmacy here, the only requirement being that you show id—although there is a limit of two packages per day. it seemed to me that the best combination was with the drink “dark and stormy,” to which i had been introduced on a visit to rhode island with mathew and jenny borland. advil cold and sinus is also used to cook “meth,” but to do so we lacked both the talent and time. alex zachary had left for “europe,” and mathew and i had the whole gallery to ourselves. i invited all my new friends over to have spaghetti. michael sanchez, amy lien, jenny borland, and of course mathew, and even heji shin came, and the bolognese worked out, as always. the next day i made lasagna from the leftover sauce in bed stuy, where i was now staying every night, actually. mornings mathew and i would go to work at the gallery; the trip took at least an hour, and you had to change trains several times and then walk pretty far.

the opening:

dear michaela,

everything is finally over. i’m so happy that it’s finished. as is often the case when things are over, i’ve really exhausted myself quite a bit, and now everything hurts. the opening was nice. jutta was there and even found mild words otherwise i was just sort of out of it. it was just much too much, and i’d also allowed myself a little drink at noon and took the advil (cold and sinus). the dinner was exactly as i had imagined it. the greyish brown and beige porridge-like food looked really appealing, and even the warm mushy consistence was satisfying. it’s exactly this kind of russian / jewish / eastern stuff that i like.

i had a piano set up, and the boyfriend of ei arakawa, sergei, who always makes music at his openings, organized a japanese pianist, who played a few 12-tone compositions. he also brought a pile of photocopies of a new york times article about himself, and from the piano he passed them out among the guests like flyers. it was really good … then it got a bit boring later, and i didn’t like the vodka (it had weird flavors like whore reddish or bulk cherry). i don’t like things like that at all … so i just ordered gin and tonics. after that we went to a bar where they wouldn’t let me in because i forgot my passport at home. mathew couldn’t get in either—too 165 drunk. we ended up back in the gallery with three friends, where i finished the rest of the drinks from the opening around ten in the morning. the next day i felt really terrible. i changed my flight to october 20—not sure what i’m going to do here until then. i also have no money at all, unfortunately—not sure how that’s going to be. certainly a bit weird. yesterday i saw an exhibition of katharina wulff and also christopher müller, who was actually pretty friendly, until i insulted his room above the berlin gallery when i said it was so similar to where i lived now, except that my room was a little bit nicer … whatever. he wanted to come by today to have a look. i have to go to queens to meet with jutta. she’s doing a performance with triple x macarena that i want to see. that’s the band with john miller and the old composer that also shows with buchholz. tonight is the thing with danh vo at artist space, and i don’t want to go, but i have to because if i don’t eat there i won’t be able to afford anything for dinner. actually, i want to go back to bed, but then comes bortolozzi, and we’re supposed to go for lunch … i haven’t had breakfast, so i wait around, and then go back to bed. i was here at this museum (www.frick.org)—it was a little bit too nice, but there were also really great paintings. i never knew exactly just how bad turner’s paintings are … why do people like them?

one painting especially appealed to me; it depicts a woman doing handicraft in a kind of cloudy haze. in the background you can see her baby. the baby looks like it’s just died, and no one is really doing anything about it. it looks really peaceful, and i’ve never seen this kind of apathy in such an old painting, although one does sometimes see it in icon paintings when mary holds baby jesus in a way that one thinks that she totally has to be on valium and is crazy annoyed with the ridiculous job of being impregnated by the holy spirit (without being asked), and now she has to be the holiest woman in the world for the rest of her life and raise this hysterical brat that’s worshipped by the whole world and is always in trouble. i wish her the best of narcotics. i need some myself